The CREST method (Climate REconstruction SofTware) is a climate

reconstruction technique that combines presence-only occurrence data

with modern climatologies to estimate the conditional responses of a

given set of taxa to a variable of interest [1-2]. The

combination of these responses is used to estimate past climate

probabilities. To illustrate the conceptual background of CREST, we will

consider fossil pollen data, as these are great, ubiquitous climate

proxies. One specific characteristic of pollen data is their limited

taxonomical resolution. Usually, pollen cannot be identified at the

species level but at a higher level (sub-genus to family level), which

complexifies the modelling of the pollen-climate responses [3].

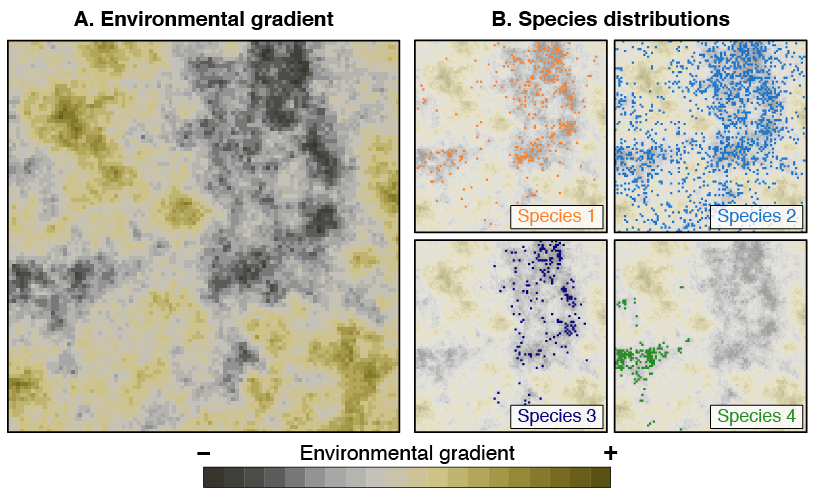

Defined as probability density functions (PDFs), these taxon-climate

responses are estimated in one or two steps based on the nature of the

proxy being studied. In simple cases, where fossils can be identified at

the species level (e.g. foraminifers, plant macrofossils), the

PDFs are defined by unimodal and parametric functions (e.g.

normal or log-normal distributions depending on the nature of the

studied variable, see [1-2] for a more detailed discussion). The

parameters (e.g. a mean and a standard deviation in the case of

a normal or log-normal distribution) describing these distributions are

estimated from the ensemble of climate values corresponding to the

presence records (Fig. 1), each being weighted as an

inverse function of its abundance in the study area. This correction

removes the influence of the heterogeneously distributed modern climate

space and ensures that the optimum exhibited by the PDF reflects the

true climatic preference of the species, rather than the modern

abundance of a given climate value [4-5].

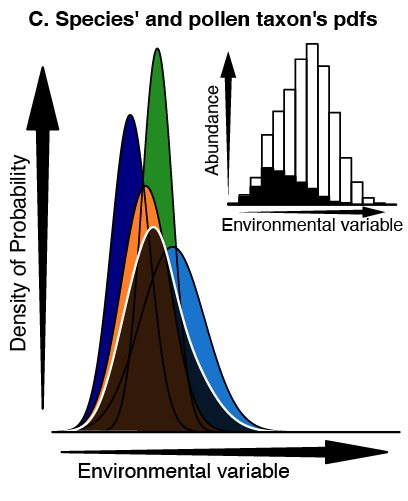

Two steps are necessary to create the taxon-climate probabilistic

link when the fossils cannot be identified at the species level

(e.g. pollen grains identified at the genus or family level).

First, following the process above, a parametric PDF is created for each

of the species producing the same type of pollen grains, and then, these

PDFs are grouped together to create a higher-order PDF representing the

pollen type, with each species being weighted as a function of the

extent of its distribution (Fig. 2). One assumption of

the model is that species with larger distributions are considered more

likely to have produced the pollen grain observed in the absence of

independent evidence. No additional assumptions are made concerning the

shapes of these pollen PDFs, thus allowing them to be multimodal if

different species/groupings exhibit different climate requirements. It

is worth noting that the process can be used with incomplete

distribution data because CREST uses parametric functions to define the

species PDFs. Reconstructions from modern [1] and fossil [6-9] data suggest that robust PDFs can still be

obtained from truncated geographical distributions, provided that the

full range of the climatic tolerance of the species is well covered in

the climate space [10].

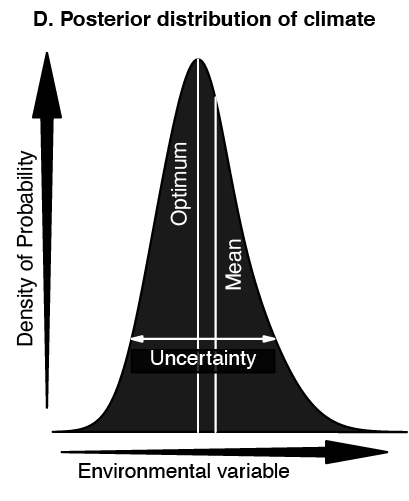

Finally, the PDFs for each fossil taxon identified in a sample are

multiplied together, each with a weight derived from the observed

percentages. Since relative abundances, different production rates and

taphonomy are important factors influencing the fossil assemblage

observed, direct percentages cannot be used directly, and they need to

be transformed to minimise the effect of these factors. In CREST, the

transformation is performed on a taxon basis by normalising the raw

percentages by the average of the percentages of all the samples where

the taxon is observed (i.e. the zeros are excluded). A value

higher (lower) than one suggests that the climate at the time of

deposition was more (less) favourable (i.e. closer to the

taxon’s climate optimum) than the average climate in which the taxon has

been observed during the studied period. The multiplication of PDFs

results in a likelihood distribution along the climate gradient, from

which climate estimates and uncertainties can be derived (Fig.

3). More technical details about the different

parameterisations of the method can be obtained from the original

publications (1-2).

Compared to other existing climate reconstruction methods, the

probabilistic nature of CREST also provides a unique opportunity to

derive probabilistic reconstructions. Such likelihood distributions

describe the likelihood of all the climate values along a studied

climate gradient and not just a single ‘best estimate’ associated with a

standard error [10]. The spread of these

uncertainties represents the amount of information available for the

studied system: well-constrained samples generally have relatively

narrower uncertainty ranges than samples with fewer constraints. This

advantage can ultimately be used in data-data comparisons and to

assimilate CREST-based reconstructions with Earth System Models

palaeo-simulations.

References

[1] Chevalier, M.,

Cheddadi, R., Chase, B.M., 2014. CREST (Climate REconstruction

SofTware): a probability density function (PDF)-based quantitative

climate reconstruction method. Clim. Past 10, 2081–2098. doi:10.5194/cp-10-2081-2014.

[2] Chevalier, M., 2022.

crestr an R package to perform probabilistic climate

reconstructions from palaeoecological datasets. Clim. Past doi:10.5194/cp-18-821-2022.

[3] Chevalier, M., 2019.

Enabling possibilities to quantify past climate from fossil assemblages

at a global scale. Global and Planetary Change, 175, pp. 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103384.

[4] Kühl, N., Gebhardt, C.,

Litt, T., Hense, A., 2002. Probability Density Functions as

Botanical-Climatological Transfer Functions for Climate Reconstruction.

Quat. Res. 58, 381–392. doi:10.1006/qres.2002.2380.

[5] Bray, P.J., Blockley,

S.P.E., Coope, G.R., Dadswell, L.F., Elias, S.A., Lowe, J.J., Pollard,

A.M., 2006. Refining mutual climatic range (MCR) quantitative estimates

of palaeotemperature using ubiquity analysis. Quat. Sci. Rev. 25,

1865–1876. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.01.023.

[6] Chevalier, M., Chase, B.M.,

2015. Southeast African records reveal a coherent shift from high- to

low-latitude forcing mechanisms along the east African margin across

last glacial–interglacial transition. Quat. Sci. Rev. 125, 117–130. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.07.009.

[7] Chevalier, M., Chase, B.M.,

2016. Determining the drivers of long-term aridity variability: a

southern African case study. J. Quat. Sci. 31, 143–151. doi:10.1002/jqs.2850.

[8] Lim, S., Chase, B.M.,

Chevalier, M., Reimer, P.J., 2016. 50,000 years of climate in the Namib

Desert, Pella, South Africa. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.

451, 197–209. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.001.

[9] Cordova, C.E., Scott,

L., Chase, B.M., Chevalier, M., 2017. Late Pleistocene-Holocene

vegetation and climate change in the Middle Kalahari, Lake Ngami,

Botswana. Quat. Sci. Rev. 171, 199–215. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.036.

[10] Chevalier, M.,

Davis, B.A.S., Heiri, O., Seppä, H., Chase, B.M., Gajewski, K.,

Lacourse, T., Telford, R.J., Finsinger, W., Guiot, J., Kühl, N.,

Maezumi, S.Y., Tipton, J.R., Carter, V.A., Brussel, T., Phelps, L.N.,

Dawson, A., Zanon, M., Vallé, F., Nolan, C., Mauri, A., de Vernal, A.,

Izumi, K., Holmström, L., Marsicek, J., Goring, S., Sommer, P.S.,

Chaput, M. and Kupriyanov, D., 2020. Pollen-based climate reconstruction

techniques for late Quaternary studies. Earth-Science Reviews, 210,

pp. 103384. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103384.